Marc Ordeix holds a PhD in Biology and is a researcher specialized in river ecology. For more than two decades, since its inception, he has been at the head of the Center for the Study of Mediterranean Rivers (CERM), at the Ter River Museum in Manlleu, which in 2016 was integrated into the University of Vic - Central University of Catalonia (UVic-UCC). In recent months, the lack of rain and the drought situation have sparked many questions in his area of expertise, and there are many unknowns about what will happen if it does not rain in the future or does not rain with the same volume as in the past

Lately, we have talked a lot about the lack of water, but not so much about its quality. What is the health status of biodiversity of rivers in Catalonia?

Right now, rivers and ponds are all below minimums in terms of water volumes. Sections that we did not imagine have dried up and others have shifted from permanent to temporary. This means that the polluting products that are already in the water have been concentrated more than ever in the little that remains, a situation that causes the deaths of aquatic animals and fish, amphibians and invertebrates of all kinds. Only the most resistant remain. It is as if there really have been toxic spills.

Would the long-awaited rain solve the problem

The water that people need (for irrigation, for the home, for industry) can be recovered with a certain amount of rain that recharges aquifers and reservoirs. And although it will be hard to achieve, it “only” needs to rain. Sometimes the life that is lost is recovered and sometimes it is not. When it rains again there are species that will have disappeared from many places. This is the problem, that much of the damage has already been done and we do not know when we can, or if we can, reverse it.

“Sometimes the life that is lost is recovered and sometimes it is not. When it rains again there are species that will have disappeared from many places”

Can we do anything to try to reverse this situation?

The point is not whether we can do anything, it is that we must do something, because doing nothing would be an even bigger social suicide than the one we are already causing. To give an example, the system of water treatment plants that we have in Catalonia, which has worked well for a long time, is now insufficient. We have to rethink what water treatment plants should be like, because with the volumes of water that are now coming down our rivers, their operation has become partially obsolete or has ceased to be operational. We have to start making decisions in which we consider that it will probably never rain again like it did before.

So, does the future involve a much more rational use of water?

We must save water, but also try to reuse what we have. We all have to do this, individually, by contributing with small actions. I stress actions as simple as collecting rainwater, if you have a vegetable garden, or not having grass in gardens: it is of no use and requires enormous water consumption. Then there is the challenge of resolving issues that have been pending for years, such as improving the efficiency of irrigation systems; stopping the use of fertilizers to replenish fields, as they end up in rivers and ponds; improving the quality of industrial and urban discharges; and managing the forest in another way, because right now we have too much in some sectors.

Is having too much forest counterproductive?

It may seem like a contradiction, especially when a biologist says it, but the situation is very clear. Until the 1940s, the forests of Catalonia were very bare, because wood was extracted for fuel, to make charcoal or to use in wooden objects, and because land was needed for extensive livestock farming. But then this use was gradually abandoned, diesel began to be adopted as fuel, intensive livestock farming started up, many people went to live in the cities and the forest was repopulated. A continuous forest landscape, especially if it is young and very dense, provides little biodiversity, increases the risk of fires and consumes a lot of water that, consequently, does not reach the rivers.

How can the work you do at CERM contribute to finding solutions to this critical situation?

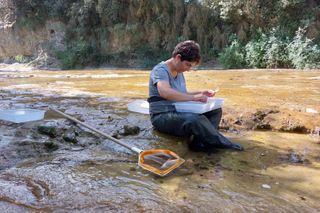

We study rivers to get to know them, but also to help manage them better than in previous generations and in line with the current situation. Recently, we supported the Catalan Water Agency in the process of emptying the Sau reservoir. We also work with companies and other entities to find sustainable solutions to water shortages in the short, medium and long term. We have even had to change the way we approach rivers to do our work, because the usual study systems have stopped working with the water flows, which are often fleeting. Another factor is the riparian forest: we try to increase its value because, although it consumes part of the water from the rivers, it is home to a lot of biodiversity and acts as a filter for pollutants from the fields towards the river and vice versa.

Periodically, and for many years, you have been conducting studies on the water quality and biodiversity of several rivers, such as the Ter. What does the evolution of these data tell us?

That although we have made a lot of effort, we are not improving biodiversity and the physicochemical and biological quality of the water. And it's not that we are doing things wrong, but our actions today are no longer sufficient. Why? Well, because we have wrecked the climate and this messed up climate affects every part of our lives. Small measures are not enough to reverse it and even now we continue with the inertia of years, using fossil fuels and water in the same way as before, without realizing the severity of the situation.

“Although we have made a lot of effort, we are not improving biodiversity and water quality; it's not that we are doing it wrong, but our actions today are no longer enough”

But CERM's scientific work has been going on for much longer than the current drought situation. How do you define your job?

We use biological indicators as quality indicators. Aquatic invertebrates, fish and vegetation are, in a way, spies: their presence or absence gives us information, from which we identify which restoration and conservation actions are recommended and we propose specific changes to town councils, institutions and companies, for example, to build a fish ramp, remove a floodgate or restore a strip of riparian forest. Our research is very applied, and even when we do purer science, what we learn ends up being used to understand things and ultimately try to solve problems.

What does this work of conservation and restoration of the environment consist of?

We establish agreements with public and private land owners, and support them to improve the management of the part of their property that is close to the river. We help them, but we also want the projects that are executed to serve as pilot tests: if we know what works best, we can replicate it or help others replicate it elsewhere. We have many examples, such as the 25 kilometres of river course and over 100 hectares of land recovered in Osona, where we even manage two islands and some of the best-preserved riverside spaces in the country, some of which have been recognized as protected (or are on the way to becoming so).

And you also explain everything you do...

This is the third main area of the CERM, alongside research and conservation, and just as important as them: education, dissemination and raising environmental awareness. From the outset, we understood that there was no point devoting ourselves to thinking and doing, if our work does not reach people. In 2022, 2,758 people attended the environmental education workshops we run at the Ter River Museum and a further 2,852 took part in activities we organize with other entities, such as Osona Nature Outings.

“The presence or absence of invertebrates, fish and vegetation are indicators of water quality, from which we identify which restoration or conservation actions are most recommended”

In September, it will be seven years since the CERM joined the UVic-UCC. How has this decision affected the Center?

In an informal way, we already had a strong relationship with the University. I taught classes in Environmental Sciences, and we had collaborated on projects with BETA. So the transition was very natural and the integration gradual. Now we have found synergies with other research groups, mainly in Education (GRECC) and Aquatic Ecology (GEA), where we have been integrated. Above all, it was very important for us to have the support of the Research and Technology Transfer Unit (OTRI): this means we work with people who are highly specialized in the management of European projects, who are also proactive in the proposal of new initiatives. The management of projects works much better this way and, without a doubt, this has made it possible for our number of projects to increase.

We can see the example clearly in knowledge transfer: in the last three years the number of projects you have been awarded has doubled.

In 2019, we had twenty projects and an income of 46,478 euros, while in 2022 we had thirty-nine projects for a total amount of 160,059 euros. The growth has been exponential, but the numbers are not everything. The most important thing is that these projects, whether big or small, have meant working for and with public administrations, institutions, educational centres and companies, in research, restoration, education and dissemination. This is the strategy that is sought, but it is also evidence of the need of all these actors and of the fact that, after twenty-two years of activity, CERM is known and valued.

What challenges is the Center facing at the moment?

The main challenge is to find a way to receive a constant amount of funding, which allows us to work effectively to achieve our main objective: the consolidation of the Center for the Study of Mediterranean Rivers as a leading entity in research, environmental education, scientific dissemination, conservation and ecological restoration of rivers and other inland aquatic environments.

A specific, crucial challenge is to renew the permanent exhibition of the Ter River Museum, which would make it possible to explain environmental values and the link between research and the territory. We have an extensive collection of over 4,000 very interesting pieces, some of great historical value, including animals and plants that have disappeared, which we cannot show to the public at this time, although they are useful for education and research. We have been part of the Network of Natural Science Museums of Catalonia for a couple of years, and we would like to be able to convert the small, modest current exhibition into an immersive and modern exhibition.

“I am optimistic because society has changed for the better, but the future will depend on what we are able to do from now on”

What will be the future of our rivers?

Those of us who work on ecological issues are a little depressed, but I am optimistic, because I can see that society has changed for the better: people know what biodiversity is and understand that you need to take care of the environment, even if it is for such a selfish matter as the survival of our species. I am convinced that our work is useful: we support society in this change, and we contribute to preserving and improving the environment. And although the results are not very good, without what those of us who work in the field do, we would be much worse off right now. The future will depend on what we can do from now on: because we can make things better, but things could also end up very badly.